While we focus on ship counts, readiness percentages, and hull maintenance, there’s another critical battle being fought in Navy Medicine laboratories that directly impacts our fleet’s combat power: the fight against antibiotic-resistant bacteria.

The Naval Medical Research Command (NMRC) just completed a six-year research program that could revolutionize how we protect our sailors and Marines from one of the most insidious threats they face—bacterial infections that laugh at our best antibiotics.

The Invisible Enemy

Here’s the reality: our warfighters aren’t just exposed to enemy fire. They face bacteria through combat injuries, deployments to overseas locations, and the close-quarters environment of shipboard life. And increasingly, these bacteria are resistant to the antibiotics we’ve relied on for decades.

Four bacterial villains are the focus: Acinetobacter baumannii (nicknamed “Iraqibacter” from the early Iraq war days), Klebsiella pneumoniae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Staphylococcus aureus. All can cause fevers, fatigue, swelling—and in severe cases, death.

When a sailor or Marine is fighting a multidrug-resistant infection, they’re not mission-ready. They’re not protecting their shipmates. They’re fighting for their life.

The Navy’s Secret Weapon: Bacteriophages

Navy Medicine Research & Development has a solution that sounds like science fiction but is brilliantly simple: use viruses that naturally hunt and kill bacteria.

Bacteriophages—or phages—are viruses that target specific bacteria with surgical precision. Unlike antibiotics that carpet-bomb your body’s bacterial ecosystem (killing both good and bad bacteria), phages are smart weapons. They go after only the harmful bacteria you want eliminated.

Over six years of focused research funded by Congressionally Directed Medical Research Programs (CDRMP), NMRC has developed approximately 2,500 phage cocktails. Think of these as personalized medicine—specific combinations designed to attack specific bacterial threats.

From Wastewater to Warfighter

The collection process is global and fascinating. Navy researchers harvest phages from wastewater—bogs, sewers, rivers—across multiple continents. These microscopic hunters are everywhere. In fact, if you strung together all the phages on Earth, they could wrap around the Milky Way Galaxy three times.

Each collected phage goes through rigorous purification and characterization. As Dr. Biswajit Biswas, chief of NMRC’s Bacteriophage Science Division, explains: “We collect these phages, purify them and grow them in large quantities. Then, we extract DNA, sequence its genome and analyze the phage very carefully to understand if it carries any toxins, since we cannot push something in the human systems if the phage carries toxins.”

This is meticulous work. This is Navy excellence.

Proof of Concept: The Tom Patterson Story

In 2015, NMRC achieved something historic. Dr. Tom Patterson fell critically ill from Acinetobacter baumannii, slipped into a coma, and remained ill through multiple treatments. Nothing worked. Until he was administered an NMRC-developed phage cocktail intravenously.

He survived.

As Dr. Biswas notes: “It should be understood that before Tom Patterson’s case, nobody used phage to treat systemic bacterial infection in the United States.”

NMRC didn’t just save a life. They opened a door.

Why This Matters for Naval Readiness

Commander Mark Simons, director of NMRC’s Infectious Diseases Directorate, gets straight to the point: “Navy and Marine Corps warfighters are often first to the fight as expeditionary units, and thus will experience early casualties in a potentially prolonged-care setting. This will require novel antimicrobial countermeasures to be used early and throughout the continuum of care to treat antibiotic-resistant infections which are rising globally and highly prevalent in developing countries and high-conflict regions.”

Read that again. First to the fight. Early casualties. Prolonged-care settings.

When we deploy our carriers to the Indo-Pacific, when we send Marines into contested environments, when we operate in regions where medical evacuation isn’t guaranteed—our people need every medical advantage we can give them.

A sailor fighting a superbug infection can’t stand watch. A Marine with a resistant wound infection can’t complete the mission. Medical readiness is operational readiness.

Joint Innovation at Its Best

This research demonstrates something we don’t celebrate enough: when Navy Medicine and Army Medicine researchers work together with focused priorities, incredible things happen. NMRC collaborated seamlessly with Walter Reed Army Institute of Research (WRAIR) and the U.S. Naval Research Laboratory.

WRAIR’s Forward Labs collected phages in Thailand, Kenya, and Georgia. Naval Medical Research Unit (NAMRU) SOUTH provided phage isolates from South America. This global network, coordinated across services, created a phage library that will serve warfighters for years to come.

This is how you build combat advantage.

Next Mission: FDA Approval

NMRC’s next objective is clear: Investigational New Drug applications with the FDA to move the most promising cocktails into phase one safety and immune response studies.

“Navy Medicine R&D is a leader in bacteriophage research so that we can bring this promising technology to clinicians and corpsman to improve battlefield survival for Sailors and Marines,” Commander Simons states.

That’s the goal. Not publications. Not academic prestige. Battlefield survival..

The Bigger Picture

We talk often about the “hollow Navy” of the 1970s—rusting ships, deferred maintenance, degraded readiness. But readiness isn’t just hull numbers and operating budgets. It’s whether our people can fight and survive when called upon.

This bacteriophage research represents the same commitment to readiness that we demand in ship maintenance, training, and logistics. It’s the Navy refusing to accept that warfighters should die from infections we could prevent or treat.

It’s innovation driven by mission necessity.

It’s medical capability that directly enables combat power.

It’s the kind of work that happens when national will, proper funding, and talented professionals align toward a clear objective: keeping our sailors and Marines ready, healthy, and lethal.

What This Teaches Us

For 250 years, Navy Medicine has delivered healthcare to warfighters “on, below, and above the sea and ashore.” This bacteriophage research continues that legacy with 21st-century tools.

But it also demonstrates something broader about naval strength: readiness is a system. Every piece matters. From hull coatings that prevent rust to phage cocktails that prevent death from resistant bacteria, it all connects.

When we advocate for a stronger Navy, we’re advocating for all of it. The ships, yes. But also the medicine, the logistics, the training, the innovation, the global partnerships that make American naval power possible.

NMRC and its partner commands have shown what’s possible when the mission is clear and the resources are provided. They’ve built a library of 2,500 phage cocktails, established processes that could save countless lives, and positioned the U.S. military to lead in a crucial medical technology.

That’s not just good science. That’s good strategy.

That’s a stronger Navy.

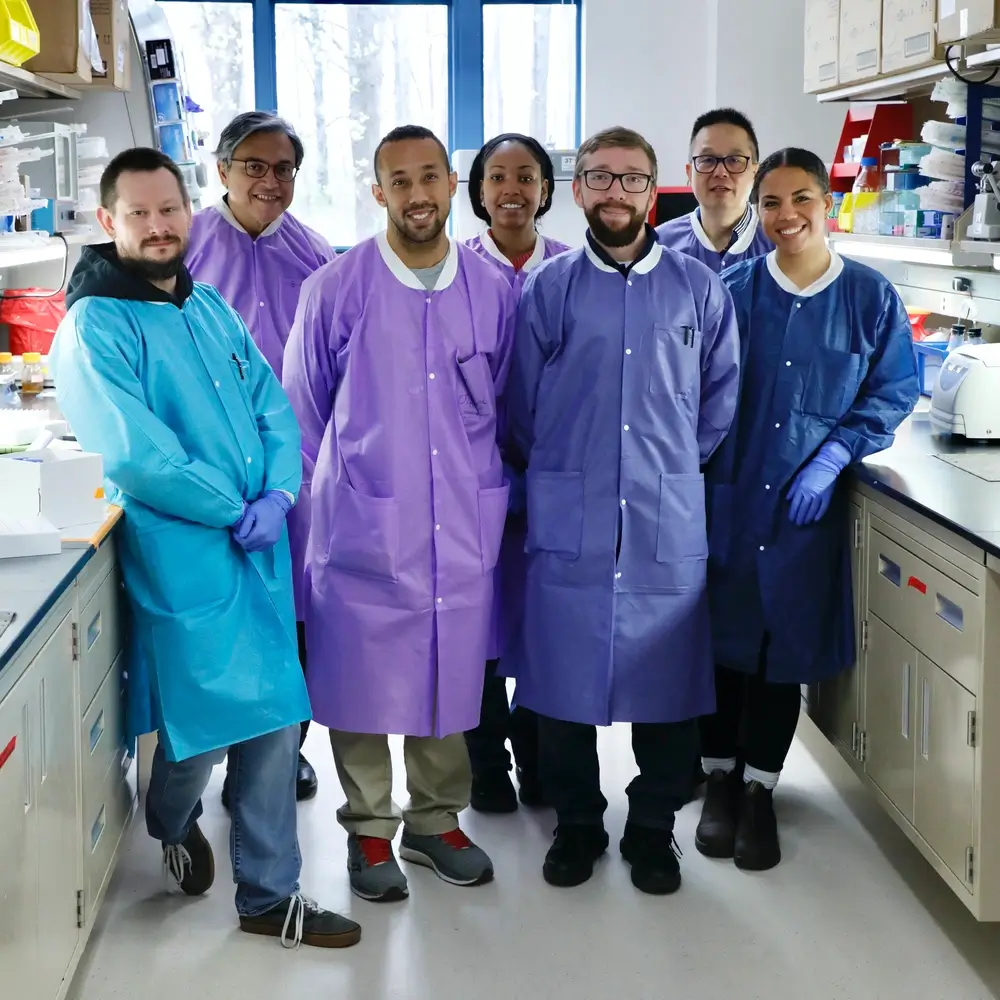

FREDERICK, Md. (April 11, 2025) Researchers with Biological Defense Research Directorate (BDRD), pose for a group photo after conducting bacteriophage therapy research to combat multidrug resistant bacteria that could impact warfighter readiness. Phages are viruses that target and kill antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Navy Medicine Research & Development (NMR&D) is engaged in bacteriophage therapy research to protect the warfighter from these threats, keeping U.S. forces ready and lethal. NMRC, headquarters of NMR&D, is engaged in a broad spectrum of activity from basic science in the laboratory to field studies in austere and remote areas of the world to investigations in operational environments. In support of Navy, Marine Corps and joint U.S. warfighter health, readiness and lethality, researchers study infectious diseases, biological warfare detection and defense, combat casualty care, environmental health concerns, aerospace and undersea medicine, operational mission support and epidemiology. For 250 years, Navy Medicine, represented by more than 44,000 highly-trained military and civilian healthcare professionals, has delivered quality healthcare and enduring expeditionary medical support to the warfighter on, below, and above the sea and ashore.

Americans for a Stronger Navy advocates for the transparent reporting, proper resourcing, and strategic innovation necessary to maintain U.S. naval superiority. Medical readiness is operational readiness. Support the sailors and Marines who stand the watch.