When Americans hear about Venezuela, they tend to think in humanitarian terms—migration, political repression, economic collapse. But that framing misses the point. Venezuela is not just a tragedy. It’s a test case for how power works in the modern world.

And power today is not primarily exercised by invading countries. It is exercised by controlling access.

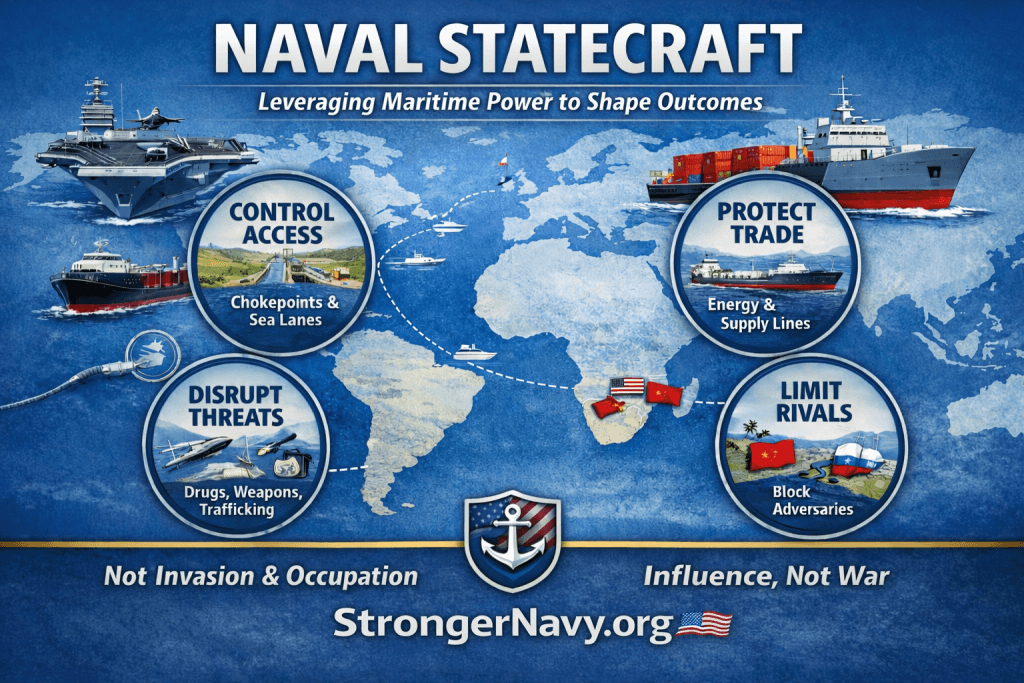

Naval strategist Brent Sadler calls this naval statecraft: the use of maritime power not to occupy territory, but to shape outcomes by controlling sea lanes, ports, trade routes, and strategic flows.

That may sound academic. It isn’t.

Oil moves by tanker. Food moves by ship. Weapons move by ship. Data moves across undersea cables. Whoever controls maritime access controls leverage over markets, pricing, and political behavior.

That is why Venezuela matters.

The country holds the largest proven oil reserves on earth. Those reserves don’t just sit in the ground—they move through ports, shipping routes, refineries, and insurance markets. If you influence those arteries, you influence global energy prices.

This is how power works now.

China, Russia, and Iran understand this. That’s why they don’t primarily project influence through armies anymore. They do it through ports, infrastructure loans, logistics hubs, shipping contracts, and maritime footholds.

This isn’t ideological. It’s commercial.

It’s about controlling the plumbing of globalization.

Most Americans still think about war in 20th-century terms: tanks crossing borders, armies seizing capitals, long occupations. Iraq and Afghanistan showed us the limits of that model—astronomical cost, endless entanglement, poor return on investment.

Naval power offers a different approach.

You don’t need to own the house to control the driveway.

Naval statecraft lets a country shape outcomes without rebuilding foreign societies, policing local politics, or stationing troops for decades. It raises the cost of destabilizing behavior. It disrupts illicit flows. It protects trade. It limits rivals’ reach.

No nation-building.

No permanent occupation.

No trillion-dollar quagmires.

Just leverage.

That matters to Americans because the modern economy is maritime. Roughly 90% of global trade moves by sea. Energy markets are maritime. Supply chains are maritime. Even the internet relies on undersea cables.

When those systems destabilize, Americans feel it—in fuel prices, grocery bills, insurance costs, and lost jobs.

The Navy doesn’t just protect territory. It protects flows.

And flows are what modern economies run on.

The public debate still frames U.S. foreign policy as a binary choice: invade or disengage. But the events in Venezuela show that this is a false choice.

Naval statecraft offers a third option.

It allows the U.S. to protect its interests without trying to govern other nations. It shapes incentives instead of regimes. It deters without occupying.

It is not warmongering. It is cost control.

It is not militarism. It is market stability.

And it has domestic benefits.

A credible naval presence requires ships, ports, dry docks, logistics networks, and skilled labor. That means long-term industrial jobs, capital investment, and manufacturing capacity—things America has been hollowing out for decades.

Naval power is not just a security asset. It is an economic one.

When rival powers build ports in the Western Hemisphere, they aren’t doing charity work. They’re building leverage. They’re shaping future trade behavior. They’re embedding themselves into supply chains.

Naval statecraft is how you counter that without turning every dispute into a war.

It is power with restraint. It is influence without occupation. It is competition without catastrophe.

And it may be the most important strategic concept Americans have never been taught.